Thursday, October 14, 2010

A FICTION WRITER'S WORKSHOP AT THE BIJOU... and a favor to ask...

Hi folks,

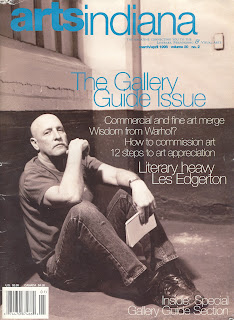

I’ve got a major favor to ask of the writers here. My agent, Chip MacGregor, is preparing to send out my proposal for a new writer’s text, titled A Fiction Writer’s Workshop at the Bijou which will use movies instead of the usual literary examples/models to inform writing techniques. We thought it would help convince publishers of the value of this proposed book if I was able to provide endorsements from writers—both published and unpublished—and students of writing, as to their opinion of the value of such a book.

Although several other movies will be included, the primary film used as the model will be Thelma and Louise. We're investigating the possibility of including a dvd of this movie along with the book.

It doesn’t matter what stage of your writing career you’re in. Beginners, seasoned pros, published authors and those still seeking your first book contract—all of your opinions will count.

I’m providing the first chapter of this book and the list of the other chapters here so you can get an idea of the scope and style of the book.

For those of you who are willing to help me out, all I need is a brief 1-3 paragraphs giving your opinion of the proposed book and how you think it might help your own writing. If you’ve read either of my previous two writer’s books, Finding Your Voice and Hooked

and Hooked , you might say something to the effect of how either of those books have helped you on your own writer’s journey. Please include your name and a brief description of your status in the writing community—author, student, etc. If you’re an author, please list your books. Some of these will probably be selected by the publisher as blurbs, with your permission, of course. If you want to write something longer, that’s great, but just a couple of short paragraphs are fine and very much appreciated.

, you might say something to the effect of how either of those books have helped you on your own writer’s journey. Please include your name and a brief description of your status in the writing community—author, student, etc. If you’re an author, please list your books. Some of these will probably be selected by the publisher as blurbs, with your permission, of course. If you want to write something longer, that’s great, but just a couple of short paragraphs are fine and very much appreciated.

Please send anything you’re willing to furnish me to my email at butchedgerton@comcast.net. If you have any questions, just send me your questions at the same address.

Thank you! We’re fairly confident this book will get taken and if it does, a big part of the reason will be the help you’re giving me here. And, please don’t think you have to be a big “name” in the biz—it’s just as valuable for a publisher to know that beginning writers see the value in such a book—after all, that’s the intended market.

Here’s the rough draft of Chapter One, followed by a list of the rest of the chapters:

I think you’ll find this chapter alone worth the price of admission to our little “theater” between the covers. The writer who can master the art and craft of defining their characters by their actions is going to be the author whose work gets read. By lots and lots of folks… Enough, hopefully, that you’ll never again have to say to someone about the novel you’ve written that it’s “only available in my room.”

* * *

A common fault of fiction writers in defining their characters and their character arcs is by neglecting to use one of the most powerful methods available. The technique? Namely, by showing the reader the nature of their character by the physical actions the writer chooses to provide their characters with. Precisely what countless writing gurus have been talking since those cave drawing days when they urged their students to: “Show, don’t tell.”

Movie people do this better than almost anyone. We can learn a lot from these Hollywood folks!

Most of us as fiction writers flesh out our characters with the use of description, via dialogue, by the interior thoughts of characters and by similar methods. All of these are good techniques and work well in the short story and novel. However, if the author ignores the use of using physical actions to help create their characters and to also show how they’ve evolved due to the events that happen along the way in the story (that character arc us writing teachers are always talking about), they’re missing what can be the most powerful tool of all. This is an area we can really make our novels come alive and impact the reader on a much deeper level.

The use of description is perhaps the weakest of the novelist’s tools in terms of creating an image of the character in the readers’ minds. What of the following makes more of an impact in the reader’s mind? To read: “Elizabeth was an arthritic old woman.” Or, to read: Elizabeth labored up the stairs, a painful step at a time. She paused at each step, grasped the handrail with both hands and forced her ancient legs up yet another step. The second example wins, hands-down. Why? Because we “see” an action the character takes and because we see it happening it has an emotional impact on us. In the first example, we’re “told” what the character is (arthritic). Doesn’t make much of an impression at all. Not even close to the impression we get when we see her forcing those gnarled knees up the stairs.

This is important enough that I’ll say it again: Characters are defined best and on a deeper level by their actions. As are their character arcs. You know, that deal where the character emerges at the end of the story a different person than when the story began as a result of all they’d gone through during the course of the tale. Why? Because they experience what the character does and what the character experiences at the same time the character does. They’re not being “told” this character has undergone a sea change and asked to take it on faith—they “see” it with their own eyes, and are therefore convinced to a degree not remotely possible with the author “telling” them there’s been a change via their thoughts or any of the other aforementioned techniques. Their actions affect readers emotionally, while descriptions only affect readers intellectually. Emotion always trumps intellect in story.

A movie that illustrates brilliantly how all this can be accomplished through the character’s actions is screenwriter Callie Khouri’s Thelma and Louise. We’ll be looking closely at this film in this chapter and others, as it’s one of those rare movies that provide many, many teaching moments that can be valuable to fiction writers.

The basic plot of Thelma and Louise, is that two friends plan to go on a weekend getaway fishing in the mountains. On the way there, they stop at a roadhouse for a quick drink or two and Thelma gets sexually attacked by Harlan in the parking lot. Louise saves her friend by putting a gun to Harlan’s head just as he’s trying to penetrate Thelma. Situation defused, Harlan just has to say one last insult and Louise shoots and kills him. The women flee the scene and the rest of the movie is basically a chase scene, ending with the women opting for suicide rather than to go prison.

The plot is fairly simple on the surface, but the characterizations Khouri has created of these people make this an extremely complex film. What is magnificent about their characterizations is that they are each revealed chiefly through their actions. Virtually every single line in the script and every moment on the screen can be studied to your gain. I’ve watched this movie more than three hundred times and each time learned something new, both from the script Khouri has created and from the brilliant work these talented actors and the director Ridley Scott bring to the project.

First, let’s look at the physical actions Khouri has given to character Thelma (as played by Geena Davis) which define her character and brilliantly carry the viewer through as she transforms into a “new” person at the end. Louise is also given actions to define her character and arc, but we’ll mostly be looking at Thelma’s. Once you’ve read this, then the script, and then watched the movie, take an extra step and go back and see how Louise’s actions inform her character as well.

* * *

The setup

* * *

We’ll begin with the “setup.” The structure of movies used to be that roughly the first ten minutes served as the “setup.” This is where the principle characters are introduced and we learn who they are and what their situation is and the inciting incident and story problem are dramatized. While this is still followed, the setup time is undergoing a major change in that it no longer takes ten minutes.

In the beginning of the setup of Thelma and Louise, there are a series of intercuts between the dual protagonists. We see Louise (played by Susan Sarandon) at her work—slinging hash in a Denny’s-type restaurant. We see Thelma at home with her emotionally-abusive and immature husband Darryl (played by Stephen Tobolowsky), a guy who’s transcended the role of male chauvinist pig to that of male chauvinist hog.

What actions does she perform that define her character? The very first one is her dialogue with Louise. The movie opens with Louise at a pay phone at the restaurant calling Thelma, asking her if she’s ready to leave on her trip. Here’s the way it looks in the script:

* * *

Louise

(at pay phone)

I hope you’re packed, little housewife, ‘cause we are outta

here tonight.

(By the way, in this snatch of dialog is virtually the only thing director Scott changed from what Khouri had written. In Khouri’s original version, Louise calls her “little sister” and Scott felt this would mislead the viewer into thinking they were sisters, so he changed it to “little housewife.” In my opinion, one of the reasons Scott is such a great director is that he doesn’t let his ego interfere by rewriting a script when the script is great, and in this case, I think he got it wrong and should have used the original version. He shows here he didn’t “trust the viewer’s intelligence to get it” unless he kind of dumbed it down. As it’s the only change he made in the entire script, I’ll give him a pass. Many directors would have changed lots more!)

As to how this works, when Louise calls her “little housewife,” this defines their relationship. As you’ll see, Louise begins in an almost “mother” role and Thelma as the child and in the very first line of dialogue in the movie, Khouri has already begun to define that relationship.)

* * *

Thelma responds with her first dialogue, which likewise immediately begins to define her character.

* * *

INT. THELMA’S KITCHEN—MORNING

Thelma

(whispering guiltily)

Well, wait now. I still have to ask Darryl if I can go.

* * *

Right off the bat, we can tell from what she says to Louise that she’s one of those “dutiful little wives.” We don’t know at this point if Darryl is her boyfriend or husband, but we do know from what she says that she feels she has to get permission from him, and that speaks volumes about their relationship, whichever it is.

But, as Louise answers her offscreen on the phone, and we hear Louise’s voice, Khouri gives Thelma a great piece of “actor’s business” (action) that really shows her character and where she’s at in her relationship with Darryl. Here’s Khouri’s action for her character (italics mine):

* * *

Thelma has the phone tucked under her chin as she cuts out coupons from the newspaper and pins them on a bulletin board already covered with them. We see various recipes torn out from women’s magazines along the lines of “101 Ways to Cook Pork.”

* * *

If that action doesn’t show us who Thelma is and what kind of person she is, nothing ever will! In less than fifteen seconds on the screen, Khouri has given us both a bit of dialogue and a specific action that deliver us a three-dimensional character and shows us exactly who she is.

Then, after she hangs up from her conversation with Louise, Thelma goes to the bottom of the stairs, leans on the banister, and yells up, “Darryl! Honey, you’d better hurry up!”

Again, with dialogue, she’s shown she’s the dutiful little wife, pandering to her husband almost as if he was a little child and she the mom urging him to get up. You can just tell that this is a daily routine and that she has to be the “mom” to her husband… and we get all this before we even see Darryl. By her dialogue and by her actions. All in about thirty seconds.

Darryl makes his appearance and Khouri defines his character also by his actions. First, by the way he’s dressed and the way he acts. Khouri gives him this appearance: Darryl comes trotting down the stairs. Polyester was made for this man and he’s dripping in “men’s” jewelry.

She further defines his character by his response to Thelma’s urging him to “hurry up.” He says, “Dammit, Thelma, don’t holler like that! Haven’t I told you I can’t stand it when you holler in the morning.”

Less than a minute has gone by in the story and we’ve already got a crystal-clear view of these two people and of their relationship. Thelma then replies (sweetly and coyly), I’m sorry, doll, I just didn’t want you to be late.”

Next, Khouri provides the character of Darryl with a very revealing bit of action that informs his character, when she writes: Darryl is checking himself out in the hall mirror and it’s obvious he likes what he sees. He exudes overconfidence for reasons that never become apparent…He is making imperceptible adjustments to his overmoussed hair. (Then, another action by Thelma that further defines her character.) Thelma watches approvingly.

In the briefest span of time, we see these two people for exactly who and what they are. All delivered via their actions (mostly) and a bit of dialogue.

Louise's character is defined even before Thelma's, in the very first scene. She's waiting tables and one of her "tops" has a group of teenaged girls, whom she admonishes for smoking, citing the well-worn chestnut that "smoking will stunt your growth." This action informs us of her character and role in the movie—that of the mother. Immediately after she's chastised the girls, she goes into the kitchen for a break and has a cigarette herself. Not only does it define her mothering character, it shows us that she's an unreliable character. She preaches one thing but does another. Pretty much what a normal parent might do!

There are countless other examples of how Callie Khouri defines each and every character by their action—virtually everything the people in her story does defines their characters. There isn’t any “actor’s business for the sake of actor’s business” anywhere in the script. These aren’t things they just “do” while delivering their lines. They do serious plot and story work.

Let’s move on.

* * *

Guns to create character arch

* * *

Tools and how characters use them are very effective ways to create a character's growth. In Thelma and Louise, one of the most important actions Khouri uses to deliver Thelma’s character arc in the story is when the two women meet at Thelma’s house to begin their trip. Thelma has elected to bring along a revolver and it’s the way she physically handles it that is a particularly brilliant piece of writing by Khouri. Thelma picks up the gun gingerly by the thumb and two fingers, obviously terrified of the weapon when she takes it out of the drawer to pack. That action is reinforced when, minutes later in the car, she reveals to Louise she's brought the weapon and she again holds it as if she's afraid it will go off and shoot her when she follows Louise's order and puts it in the older woman's purse. By the end of the story, she’s whipping the gun around like Doc Holliday’s been mentoring her out behind the O.K. Corral. This one simple action and the way it evolves during the story by itself beautifully shows the viewer how far Thelma’s come and how she’s emerged as a much different person as a result of what she’s undergone.

* * *

Smoking to show character arc

* * *

However, Khouri doesn’t use just this one action to create a character arc for Thelma. Smoking is another one. We've already talked about Louise toking on a cigarette after she's admonished the teenagers for smoking. At the beginning of the trip, Thelma pantomimes smoking a cigarette, imitating the older and more world-weary Louise. The action is of a child, imitating an adult. As events progress, she eventually becomes a true pro, chain-smoking to beat the band and looking like she’s been at it since she was twelve and a half.

The physical action of smoking is used in many places in this movie to symbolize important points. For instance, after their money has been stolen by J.R. (played by Brad Pitt), Louise has completely given up. Rather than “tell” us she’s quit the good fight, via some awkward dialogue, Khouri uses the physical action of smoking to show us. Waiting in the car, while Thelma goes into a convenience store/gas station (which she’s going to hold up, unbeknownst to Louise), she lights up, takes a desultory half-drag and then tosses the cigarette away. More than any dialogue ever could, this simple action of resignation shows the audience exactly the level of despair Louise has sunk to. She’s given up the only pleasure she had left in life (smoking). A second or two later, she takes out a tube of lipstick and begins to apply it, almost as a lifelong habit in her role as a “woman,” only to toss that away as well. Hard on the heels of giving up smoking, she’s now given up any pretense of being what society deems a woman should be as well as her very life, symbolically. With these two simple actions, we are completely convinced of the complete despair Louise feels. She’s stripped bare of everything. Her old life and old person is gone. It's at this point that she begins to achieve true independence. Only by giving up her old life can she proclaim her right to freedom from the tyranny she's lived under all of her life... from men in particular and from society in general.

* * *

Packing

* * *

In the setup, both women pack for their camping trip to the mountains. There is a vast contrast to their packing "styles" which serves to further define their characters by that action. Louise, the "mom" is in control. She wraps garments in individual plastic containers and arranges them neatly in her suitcase. Thelma, in contrast, throws handfuls of clothes into her suitcase and at one point, just dumps her drawers into her suitcase. She's definitely not in control of her life, as evidenced by her chaotic packing method. It mirrors her existence, just as Louise's style does hers. If you knew nothing about either woman, as soon as you saw each of them pack, you'd make the firm conclusion that one was in complete charge of herself and the other was more than a little "scattered." You wouldn't have to hear either of them speak or do anything else to figure this out.

Over and over, actions show us both women and how they evolve. In the beginning, Louise is not only a control freak, she's also obsessed with cleanliness. In fact, there's a scene when the antagonist Hal (played by Harvey Keitel) breaks into Louise's apartment runs his finger over a table surface, looking for dust and there isn't any.

Another scene that reinforces her neatness jones (which is really about the control she practices for her life), is when the women are waiting for drovers to get a herd of cattle around them. "Don't you scratch my car!" Louise screams at the men. Later, when they've achieved their freedom, her car is dirty, dusty and just downright filthy... and she doesn't even notice it. Evidence again that her character has evolved.

* * *

Hair

* * *

Huh? you say. (I heard you.) How is hair a physical action?

Let's take a look.

Remember at the beginning, Khouri has established Louise as the "in-control" mother (adult) figure and Thelma as the scattered, undisciplined "child." Louise packs carefully; Thelma tosses her things willy-nilly into the suitcase. Louise smokes; Thelma chomps on a candy bar. Thelma is terrified of guns and Louise is an old hand at firearms. And so on.

Now, look at their hair when the trip begins. Louise's is neat and pinned up. Under firm control. Thelma's hangs loose and free. Hair is important in this movie. Not only does it reflect the individual character at the moment, it also reveals the state of the relationship between the two women at a given point in the plot.

As the story progresses, Louise's hair begins to come down at various plot points. As she inches closer and closer to her freedom from men, the hair comes down, little by little. I won't go into every single scene where hair plays a role, although it does in just about all of them—watch the movie and focus only on the hair and the times when it is up or down or in-between on each woman and you can quickly see how hair affects what's going on and the present state of their relationship with each other.

There is a point, two-thirds through the film, when the two women reverse their roles. Thelma becomes the mother, the one in control, and Louise reverts to being a helpless child. Shortly after that, the two begin to move toward equality and their hair symbolically reflects that stage perfectly, in that both women are driving down the road and both have their hair partly "up" in the exact same "do." Not only that, but to further strengthen their new-found equality, they are both singing along in perfect harmony to a song on the radio. All actions.

* * *

Spitbath

* * *

Let's imagine a hypothetical scene. A mother has just picked up her little girl at the playground and they have to be at the girl's best friend's house for her birthday party. The woman's daughter has grime on her face from the dusty playground. What does the mother do? Why, she gives her a spitbath, of course. That's just what moms do! I know from (painfully embarrassing) personal experience. Who among us hasn't been a player in this familiar drama!

Look at the scene immediately following the killing of Harlan. They're fleeing the scene and then Louise orders Thelma to pull over. Thelma's got gore on her cheeks from the bloody nose Harlan gave her when he slapped her during his attempted rape. What does Louise do? (After she throws up of course, and re-enters the car, ordering Thelma back to the passenger side.) She gives her a spitbath, an action right out of Parenting 101! You can find it on page three.

* * *

Sex

* * *

I saw your eyes light up at this topic heading. Don't deny it. Just means you're normal.

Sex is powerful, isn't it. We pay attention when we encounter sex on the screen or among the pages of a novel.

Many writers write sizzling sex scenes that are definitely worth the price of admission. But... most of the time, those scenes don't do all that they could. Khouri gets Prius mileage out of her big sex scene, the one where Thelma and J.R. (Brad Pitt) make love. As Janet Burroway tells us in her wonderful book, Writing Fiction (the most widely-used writing textbook used in America), that character changes must always be occasioned by a physical event. Khouri uses this maxim brilliantly.

Up until the point when J.R. steals their money, Louise is in charge—the parent—and Thelma is the child. When they run to the motel room and find out J.R.'s stolen all their money, a role reversal takes place. Louise gives up and reverts to being the child—all hope is gone in her eyes. It is then that a miracle happens. Thelma becomes the parent in charge. (Incidentally, this scene is foreshadowed by an earlier scene in a similar motel room, when Thelma collapses on the bed in tears, clearly the child, and Louise takes charge.) It's Thelma's coming-of-age moment.

How can Thelma change this drastically? Remember, character change must be caused by something physical that happens to the character. Have you guessed what the physical action was that allowed Thelma to do a 180?

Sex.

That's right. But... not just any old sex. After all, she's been married four years and dated her husband Darryl for the four years of high school before that and has had lots of sex. But, what J.R. and she had was a different kind of sex for her. It was adult, mature sex. Not the version of teenager backseat dalliances she engaged in with her husband in high school and then transported to the marital bed. No, this was grownup sex. Sex between adults who approach the act as equals. And, it was because of this that she transformed into an adult and was able to take charge. Without this kind of sex, she would no doubt have stayed the child she was and would have most likely collapsed in surrender and defeat on the bed right along with Louise, as she'd already done in previous scenes in one way or another up to that moment.

This is the biggest turning point in the movie and the most dramatic moment and Khouri does it up right. First, she makes sure Thelma's defining moment isn't obscured by anything. Louise leaves their room first and it's clear she's going to be having sex herself with her boyfriend Jimmy (the Michael Madsen character). But... we never see even a glimpse of these two between the sheets doing the nasty. Why? Because Khouri wanted to make sure that the most important scene in the story wasn't obscured or overshadowed in the least which it might have been if we'd been witness to both women and their lovemaking. She’s also being faithful to keeping the story firmly in Thelma’s pov.

+ * *

There are other actions in this fine film that the screenwriter Khouri employs, but these should give you a very good idea of not only how to use such actions to inform your character and his or her developmental arc, but how vital providing them is. In the last chapter, during which we’ll follow the movie frame by frame, I’ll reveal more of these defining actions.

Now. How might we use these techniques for our fiction? Good question! Here's some suggestions.

* * *

Proscription

* * *

Since Thelma and Louise first hit the movie theaters in 1987, the country has undergone a universal negative change in its attitude toward smoking. That means that it's probably best not to adopt Khouri's ingenious use of cigarettes in your story in an anti-smoking climate. What's kind of interesting is that while smoking has mostly vanished from movies, when it does appear, mostly it signals that this is a "bad guy." Instead of wearing black, the villain these days is puffing on a Marlboro Red. What might you substitute? Well, there are any number of possibilities.

Let's say you're writing a coming-of-age novel or at least a novel with coming-of-age elements and you want something like Khouri's symbol to show the passage of your character from childhood into adulthood. What are some artifacts or actions that we associate primarily with adults and not with children?

One that comes to mind is drinking. If you watched the movie, you'll recall how Khouri has Thelma buying whiskey in those little "miniatures" when she was in her role as a child. That's how a kid might buy booze. When she "grew up" after experiencing "adult sex" with J.R., she switched to regular(adult)-sized bottles. To show your character as achieving adulthood you might show her switching from flavored vodkas to regular martinis, or you might set him up by having him order drinks mixed with colas—say a rum and Coke—to a Jack and water. (Although there seem to be plenty of adults who still enjoy pop in their adult beverages...) A better example might be having your character always running around in t-shirts with athletes' names on the back. To show he's achieved maturity, you could have him toss his Michael Jordan tees and begin wearing shirts without logos or jocks' names on the back. I heard a radio dj commenting on this one day and open it up for discussion among his listeners and the consensus reached was that after the age of thirty, a man just looks silly walking around with another guy's name on his shirt.

The point is to be observant and see what actions kids make that adults don't. In one of my short stories, "Blue Skies," the protagonist experienced an epiphany when he noticed that his mentally-challenged daughter Celsi still ate her sandwiches that were cut diagonally by taking the first bite from the center. He knew she was never going to get better when he and his wife and Celsi were out for her sixteenth birthday and she still took her first bite out of the middle. His observation was that most adults he observed always bit the tip of the sandwich off first.

There are plenty of examples around. Just be observant and you'll find them.

And don't limit yourself to just coming-of-age actions. Use actions for every significant change in your character. For instance, you may want to write a story about a man who has terminal cancer and your story is about the stages such a person might go through in coming to terms with his fate.

Let's say that right after "Charley" learns of his impending doom, he goes through a period of utter hopelessness. From that he segues into a kind of hysterical hedonism, where he does everything he's always wanted to do, but was too conservative to do while healthy. From that you may have him moving on to a period in which he takes huge risks with his life. Maybe you have him buy a motorcycle—something he's always wanted but didn't for a couple of reasons. One, he was simply afraid of motorcycles, and two, he didn't feel the family's budget could accommodate one. Now that he's only got months to live, he races out and plunks down a check for a new Harley Sportster. His wife is beside herself. He tears through town at breakneck speed, at little or no concern for his safety. She's really worried because he refuses to buy a helmet. She even goes out and buys him one for his birthday present, but he never puts it on.

And then, something happens. He has an epiphany. (What the epiphany is and how he gets it is your job—you didn't think I was going to write the whole darned thing, did you?) Something happens that somehow gives him hope and makes him come back to earth and realize that even though he's terminal, he's still responsible for his family and that if he were to get in a wreck and survive, the hospital bills might just finish off what little savings they have left. He also gains a small ray of hope that the doctors may be wrong—that he may somehow beat the death sentence.

To show his realization by a physical act, you can have him go to the garage where he's discarded his wife's present and strap on the helmet. He's really grown here, by this kind of action. He didn't revert to where he was before—he's still going to ride his cycle and he isn't overly afraid to do so—but he's going to do it responsibly now.

See how this physical action stuff works? It's kind of cool, isn't it!

Now. Go out and figure out your own actions to give your characters. Your stories will resonate as they never have before.

These are the other proposed chapters:

SECTION I: Characterization

Chapter 1: Characterization. How actions both inform characterization and provide a dynamic means to create character arc.

Create Memorable 3-D Characters

Giving your characters physical actions to define characters and show character arc.

Physical actions to create character arc.

Actor’s “business” and how it can help or hurt.

How exposition is handled through the “back door” by using details to show character traits without pushing the information into the readers’ faces. (This chapter included)

Chapter 2: Protagonists and Antagonists.

Protagonists and antagonists and supporting characters and how their roles work in story. Creating sympathy for the protagonist by piling on trouble. Point-of-view. The multiple povs used in T&L.

Chapter 3: Dialogue That Rocks

Dialogue that cooks and sears deeply into the retina of our souls. Why and how "off-the-nose" dialogue works and why "info dumps" and "Q and A" dialogue constructs don't. The value of as well as the danger of using movie dialog as a model for fiction—the things that can prove profitable in writing better dialog and the elements that may be detrimental when not knowing how to look at dialog, including how the “values” of a movie (lighting, big-screen, etc.) can amplify dialog in a way print cannot. How subtext provides the highest form of dialog.

A common misconception: Why many times film dialogue doesn't work in a fiction setting and shouldn't be used as a model (a look at how production values can distort the value of a film example.)

Chapter 4: Emotional response.

Understated works better than melodrama. Lowering the volume creates drama; raising it creates melodrama.

The "daydream" vs the Jungian "nightdream": how one is based on cheap sentimentality and the second on honest, earned emotion.

Chapter 5: Activate the Six Senses

What senses are being neglected? A fool-proof exercise to include all five.

SECTION II: Story Structure

Chapter 6: Structure Your Novel Like a Movie

Three-act structure of drama works for the novel

Inciting incidents. How a plot is created via causal events.

Chapter 7: Set The Mood

Where in the world are we? Give enough details to establish time and place, then allow readers to make their own “leaps.”

Chapter 8: Backstory/setup.

How backstory—the "kiss of death" in a novel if this is the first thing the reader encounters—is handled in the hands of a master like Callie Khouri in Thelma & Louise.

Chapter 9: How to Write Riveting Scenes

Enter late and leave early. How to set future scenes up by foreshadowing.

Chapter 10: Apply the Principles of Mise en Scene to Your Novel

How to utilize setting to define character.

Create opposing settings that powerfully illustrate character contrasts.

Use specified “visual” evidence to show how the use of space changes over time. Using weather as a “character.”

How a building can influence a story.

Chapter 11: Transitions

How transitions have changed in fiction, chiefly due to movies. In the "olden days" of filmdom, transitions were handled much as they were in fiction; with subtitles and formal "pronouncements" on placards that, "Now, we are leaving Mary Jane and her troubles with her father and traveling back to where all the conflict began, back in her childhood." Nowadays, there are no transitions as in days of yore, because today the movies just "goes" to the next scene (jump cuts), sans any explanation or lead-in, and audiences have learned to adjust and "get" what's happening. Fiction needs to do the same thing (and the good stories do), but alas, many teachers still drum archaic transitional techniques into their students' heads, at the expense of having their stories fail due to the musty, "old-timey" feel of the fictions utilizing such techniques.

Chapter 12: Surface-problem and story-worthy problem.

How each is related and resolved. How the story-worthy problem is not made manifest to the protagonist until very near the end and how the viewer/reader may not even be conscious of the story-worthy problem, but instead many times assimilates it subconsciously. Why even though the reader may not be aware of the story-worthy problem, the author has to be.

Chapter 13: Create Story Endings that Pack a Punch and Resonate with the Reader

Write resolutions that satisfy emotionally. How good endings contain both a win and a loss for the protagonist.

SECTION III: What Helps Sell Your Fiction

Chapter 14: Create “Sizzle” in Your Novel

Learn how Hollywood creates buzz

What a “set piece” is and how they’re constructed

Why “watercooler moments” are the easiest way to sell your novel and absolutely essential in creating a bestseller.

How to use those moments to sell your novel to an agent

How to create 3-8 “set pieces” or “watercooler moments”

Examination of eight watercooler moments from Thelma and Louise

Create “Aha!” moments and “inside information” for your readers to discover.

How subtleties in your novel can tremendously improve its complexity and appeal for discerning readers.

Chapter 15: Take a Tip From the Movie Moguls—Pitch Like a Pro

Pitch like the pros: What to do—and what to avoid when you meet with an agent to pitch your novel.

Real life examples of successful—and unsuccessful—pitch meetings.

Create titles that sizzle. Short is usually best. Follow the lead of movie marketing wherein titles are usually created with brevity in mind (to fit on the marquee and also to provide a short title that’s easy to remember when people are talking about it).

SECTION IV

Chapter 16: Watching the movie, frame-by-frame.

Here, we’ll go through the entire movie as it plays, noting the important elements as we’ve learned them in the preceding chapters and observe how it all comes together to create a story.

Epilogue

Index

Thank you so very much! I've been working on this book for over ten years and I truly think this can be a book writers will find valuable.

Blue skies,

Les

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

9 comments:

Hi, Les! I'll read this chapter tonight or tomorrow morning and try to get something to you by the end of the day tomorrow. I should have a nice chunk of time in the early afternoon. :-)

I'm excited to hear you'll be releasing another great tool for us!

Great idea using movies as examples! I love the way Robert McKee did this in his screenwriting book STORY, even if it did spoil the plot of Chinatown for me.

Thanks Shannon and Lynne!

Anything you guys can send me will be HUGELY appreciated!

I've been using movies for almost 15 years in the classroom to inform fiction techniques and I've just found it's far more effective than novels. Some are a bit elitist and don't think we can learn from movies, but I disagree strongly.

I'm in! I'd be honored to do this. Because I underlined so much in my copy of Hooked I had to go out and buy a second copy. And because I love the idea of this - I remember reading what you wrote in Hooked about jump cuts and what they meant, so to speak, for the change in audiences and thus the change in what is acceptable in fiction. I loved that,and I'm so glad you're going to expand on this.

I'll read and have a piece to you tomorrow. Thanks for the opportunity to put my two cents worth in on this killer good idea.

Thank you so much, Robin!

All of you guys' generosity is humbling.

And... a person who buys TWO copies of one of my books... I'm in love!

Les,

It already looks like it will be up there with 'Hooked.'A forth book in my library that I won't loan out. Too many of my own comments written in and not willing to write without it as a quick reference.

I'll start writing a couple of paragraphs tonight. Might not send it on until tomorrow.

Do you have a date for release? I'm struggling with some tough scenes right now, and if I could, I'd be using it.

Les,

It already looks like it will be up there with 'Hooked.'A forth book in my library that I won't loan out. Too many of my own comments written in and not willing to write without it as a quick reference.

I'll start writing a couple of paragraphs tonight. Might not send it on until tomorrow.

Do you have a date for release? I'm struggling with some tough scenes right now, and if I could, I'd be using it.

Dude - what can I say - a great idea executed brilliantly. What I've read has been so useful already ... anyway, I sat down to write a review but it's so gushing with praise as to be unbelievable. I'll leave it to the 'pros'. What I can say is, after reading this, I'm ordering Hooked and Finding Your Voice asap. Heaps of luck with this - not that you'll need it.

Carson, take care of your own writing first! But, when you do catch a break, I'd love an endorsement from you. We're sending it out in the next several days but whenever you can is fine as I'll just add it to future submissions to editors.

Gary... let me get this straight--you wrote something that was "gushing with praise" but not sending it and leaving it to the pros? Dude! This is exactly what I need! Please send it and I'll cover up my eyes in embarrassment. Your opinion counts very, very much. It's a book intended for the beginning writer as well as for the seasoned one. Your opinion is very valuable to me and will carry weight with publishers as being from a person who is the intended market, so I hope you'll reconsider.

You guys are great!

Post a Comment